Book Scorpions & Why You Should Love Them

October 31 2021

If you were to flip open a book and find yourself facing what looks like a really tiny scorpion without a stinger traipsing around a page of the book, you might (quite understandably) scream bloody murder and a few choice bleep-worthy words that would make even a drunk sailor on shore leave blush.

And you wouldn’t be entirely wrong to have such a reaction -- when it comes to scorpions, the smaller they are, the more dangerous they are (because the smaller they are the less they can rely on their pincers for protection and hunting, so the more potent their poison has to be).

Luckily, however, what you’ve encountered doesn’t have a stinger, so it’s not a true scorpion, but rather a pseudoscorpion.

It’d be impressive if you ever saw one, because when we say these little dudes are tiny we mean tiiiiny. The biggest species (which is found in Ascension Island) can grow to a whopping… 12 mm long. Most species range from around 2-8 mm.

Like we said, they’re tiny.

In fact, it’s possible you might’ve even seen one before on your bathroom sink and confused it with a hilariously tiny spider. Household pseudoscorpions are more visible when in the bathroom sink, but are most famously found inside books, which has earned them the nickname of “book scorpions”. ‘Cause, y’know, they’re in books and look like scorpions.

If you do come across a book scorpion, don’t kill it.

We bookworms are fans of the book scorpion.

...Well, we metaphorical bookworms are fans of the book scorpion.

Literal bookworms are probably less enthused about having them as neighbours, seeing as they’re a favourite book scorpion snack (which, ironically, is the reason we metaphorical bookworms like them so much -- they’re fantastic helpers for book conservation!).

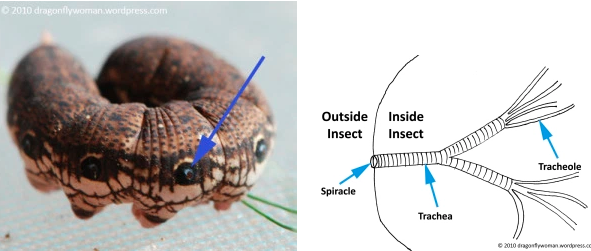

To ramp up the irony even further, one of the reasons book scorpions aren’t true scorpions is that they breathe by way of spiracles rather than book lungs, (a kind of primitive lung unrelated to our own lungs but that ultimately serve the same function; to learn more about this, see the end of the post).

Book scorpions also eat other small parasites like mites, clothes moth larvae, and carpet beetle larvae, so even if you find one far away from your books they’re definitely worth keeping around.

Final fun fact on these little guys: The first recorded mention of them can be found in Aristotle's De historia animalium, which is considered to be the founding work for descriptive zoology.

=-=-=-=

Spiracles are little holes on the exoskeleton of some bugs that lead to a windpipe that supplies oxygen directly to the animal’s tissues through a system of tubes much like how our arteries would.

Both the images above were taken from this blog post by Dragonfly Woman (aka Chris Goforth, Head of Citizen Science at North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences & @DragonflyWoman2 on Twitter) about how insects breathe which explains how piracles work in a very approachable manner. If you’re confused about how they work or want to learn more, it’s definitely worth a read.

Book lungs got their name from the fact that they’re made up of hundreds of thin layers of tissue that absorb oxygen into the scorpion equivalent of blood, which look a lot like pages in a closed book:

The book lung images above are screenshots from Episode 1 of BBC’s 2005 docuseries Walking With Monsters: Life Before the Dinosaurs (from a segment about an extinct genus of scorpion called brontoscorpion).

By Alice Flecha (Volunteer Blogger)